The directional policy matrix (DPM) is a strategic policy-making instrument.

A corporation with multiple business divisions may wish to know which should be invested in and which should be disposed of. Product managers may be in charge of a portfolio of goods with varying levels of performance and opportunity. Which of these goods will be the most powerful in the future, and which should be avoided? The Boston matrix (see Chapter 8) is a good tool for this investigation, as is the directional policy matrix.

Marketers regard the directional policy matrix as a critical business model for directing segmentation strategies. Customers are not all the same, yet there are certain similarities. ‘Segmentation’ refers to the process of categorising clients based on their differences and similarities.

A segment is a group of clients who have common qualities related to the product or service they are purchasing.

Segmentation is fundamental to every marketing plan since it allows a company to better meet the needs of customers and so please them. It is also advantageous to the firm providing the products and services since it can group clients to satisfy their needs rather than treating them as individuals. As a result, the supplier gains higher economies while also getting a competitive advantage by providing groups of clients in a manner that may provide it with a competitive advantage.

There are many different ways in which customers can be segmented. Common themes are as follows:

Physical characteristics:

- Demographics: gender, age, geographical domicile, social class, income group, family size, and so on.

- Firmographics: (for B2B companies) the size of the company in terms of employees and revenue, the industry classification of the company, the company’s age, its geographical location, and so on.

Behavioural characteristics:

- customer or potential customer, or a lapsed or returning consumer.

- purchasing patterns: frequency of purchase, amount purchased, product bundles purchased, and so on.

- consumption behaviour: amount of product consumed, how it is eaten, where it is consumed, and so on.

- supplier behaviour: single sourcing, dual sourcing, supplier loyalty, frequent switching, and so on.

- decision-making behaviour: the number of persons in the decision-making unit, their status, key decision-makers, and influences.

Needs:

- essential needs for the offer, such as quality, durability, convenience of use, availability, price, technical support, and so on.

- emotional demands of the supplier and brand: status, reassurance, excitement, safety.

psychographics:

- customers’ lifestyle, values, opinions, attitudes, and interests.

Good segmentation seeks to identify groups of customers who share common traits and are likely to be the most lucrative or have the greatest development potential.

The directional policy matrix is a tool for deciding how to invest in various chances.

It is frequently used to demonstrate the strategic attractiveness of various segments, but it could also be used to influence policy on brands, business units, new product opportunities, and nearly any other collection of options that a firm might need to examine. It is based on two elements, as mentioned below: the segment’s position in terms of profitability potential and the segment’s competitive position.

Attractiveness of the market

When contemplating any future investment, the anticipated profitability of a segment (or business unit, or product) is a crucial consideration. A low-profit prospect would imply no investment. This prediction may be subject to some uncertainty. If a competitor withdraws from the market, the situation may alter. New or forthcoming legislation that benefits a specific industry or product may cast a different light on the situation. These elements should be incorporated into the evaluation.

Other aspects to consider when evaluating the market’s attractiveness include the segment’s growth prospects, the number of competitors in the industry, and their respective strengths and weaknesses.

Competitive capability

The competitive capability assesses the company’s other segment suppliers. The strength of the company’s customer value offer within the category in comparison to competitors will determine its competitiveness. The strength of the brand and customer loyalty may also be considered, as could its production units, their age and productivity, patent ownership, ability to innovate, and so on.

It is worthwhile to use a market intelligence-based measure when mapping market attractiveness and the company’s competitive capabilities.

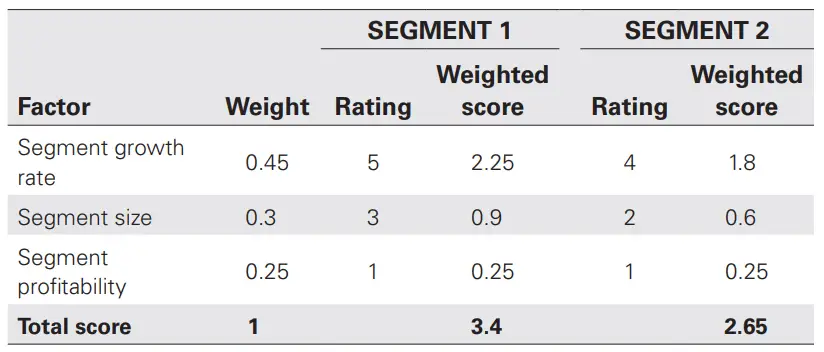

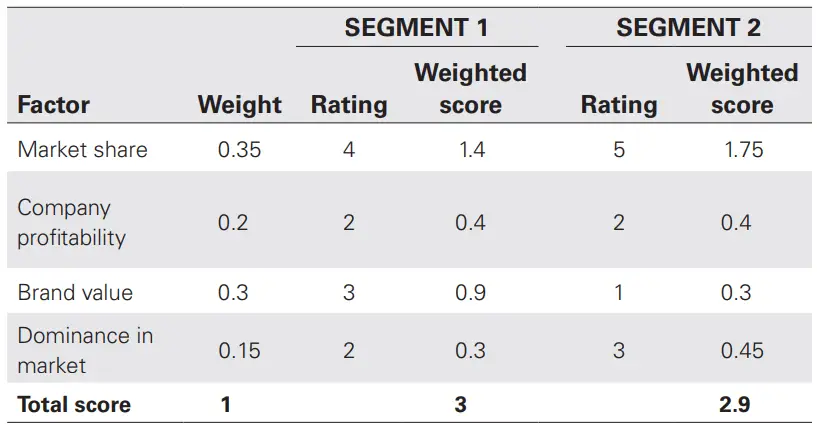

The application of a weight or rating will sharpen the positioning and turn it into a metric that may be changed as circumstances change. When calculating the attractiveness of a market, for example, a list of all the variables that make it appealing is created, including growth rates, sector size, profitability, price elasticity, regulation, and so on. Each of these is ranked in order of importance. The segments are then scored (say, on a scale of 1 to 5, with 5 being strong and 1 being weak), and a weighted score is calculated. Weights for competitive positions can be generated similarly. See tables 1 and 2.

The directional policy matrix is a tool for prioritisation. The two dimensions of industry attractiveness and business strength assist managers in focusing on the most important concerns. It points in a strategic direction; therefore, it is action-oriented, which should lead to a more profitable organisation.

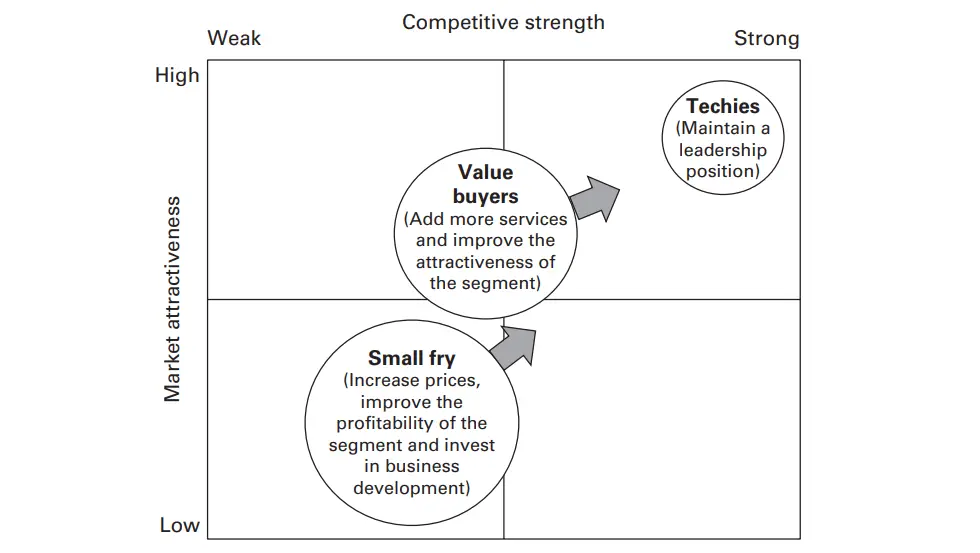

Possible strategic directions are given when the weighted scores are placed on a grid with the market attractiveness as the Y axis and the business unit strength as the X axis. Segment 1 in Tables 1 and 2 has a medium-to-high market attractiveness and a medium-to-high competitive position. This suggests a possibility for investment and brand development. Segment 2, on the other hand, has a substantially lower market attractiveness score despite having a rather good competitive position. This signals a potential brand-harvesting approach.

Brands with a low competitive position yet located in an appealing market may find it worthwhile to try to discover a niche in which to focus. A brand with a strong competitive position but operating in an unappealing market may be worth defending and refocusing on. As one may expect, a brand with a low competitive position and market attractiveness should be removed from the portfolio.

Strategies for directional policy matrix model

- High market attractiveness and strong competitive strength: invest in trademark protection.

- High market attractiveness/medium competitive strength: engage in brand development.

- High market attractiveness/weak competitive strength: target certain segments with the brand.

- Medium market attractiveness/strong competitive strength: selectively create the brand.

- Medium market attractiveness/medium competitive strength: Harvest the brand.

- Medium market attractiveness/weak competition strength: selectively target or harvest the brand.

- Low market attractiveness/high competitiveness: protect or refocus the brand.

- Low market attractiveness/moderate competitive strength: Obtain the brand.

- Low market appeal/weak competitive strength: Consider removing the brand.

Benefits and When to Use Directional Policy Matrix Model

- Focus your plan by using the directed policy matrix.

- The greatest potential is usually connected with increasing your competitive strength (as was the case in Figure 3 with the’small fry’ and the ‘value purchasers’). This necessitates an understanding of your own strengths and flaws.

- Use a SWOT analysis in conjunction with the directional policy matrix.

Wow, this post is pleasant, my sister is analyzing these

kinds of things, thus I am going to convey her.

Greetings from Florida! I’m bored at work so I decided to check out your site

on my iphone during lunch break. I really like the information you present here and can’t wait to take a look when I get home.

I’m shocked at how quick your blog loaded on my phone ..

I’m not even using WIFI, just 3G .. Anyhow, good blog!