We all enjoy trying something new. The word “new” is one of the most powerful in the marketing vocabulary. It promises advancements. It connotes excitement. Nonetheless, we all respond to ‘new’ in different ways. Some of us are desperate to get our hands on a new product. We love ‘new’ because of the benefits it provides and the status it conveys. Similarly, some of us are afraid of the ‘new’. Experience has taught us that it frequently fails to deliver what we hoped and desired, so we prefer to stick to what we know.

As a result, new products and services are not welcomed by everyone in the same way. When an innovation is introduced into a market, it spreads quickly to some people and slowly to others. Several theories have been proposed to explain the process by which a new idea or product is accepted, as mentioned below.

The two-step process

According to this theory, new products and ideas are accepted first by a small group of people known as opinion leaders. These individuals are critical to the spread of the new product because if they like it, they will promote it and the general public will accept it. This is evident in markets where the voice of the opinion leader is highly valued. Journalists review new cars, and their comments can have a significant impact on the launch’s success. Theatre critics have the power to make or break a new musical or play. Within organisations, there are gurus whose opinions on new products influence those who work with them.

The trickle-down effect

Many new products are initially prohibitively expensive. They are only available to the wealthy or privileged few. This may give the product status in the eyes of the general public, who are waiting for the price of the product to fall and become more affordable. The first mobile phones were expensive and the size of a brick, and they were only available to those with a high income or a high position in politics or business. As the prices fell, they became more affordable to everyone, including schoolchildren.

The diffusion of innovation

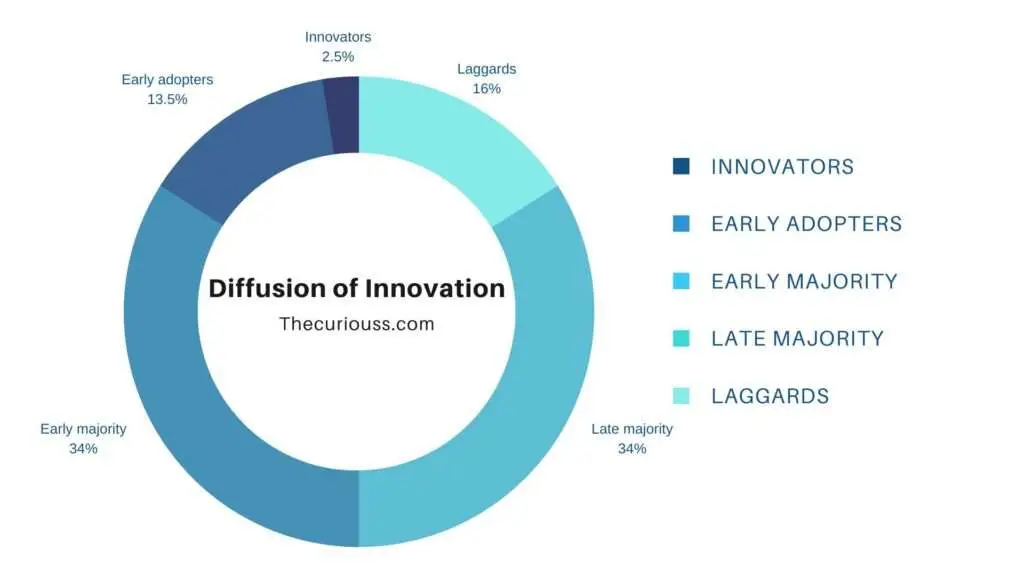

The diffusion of innovation theory is a framework that explains how new ideas, products, and technologies spread through a population over time. Developed by sociologist Everett Rogers in the 1960s, the theory suggests that the adoption of new innovations follows a predictable pattern that can be divided into five stages:

Innovators (2.5 percent of the population) are people who are always eager to be the first to own a new product. These individuals are risk takers who aspire to be seen as leaders. The first group to adopt a new innovation typically comprised of risk-takers, visionaries, and early adopters.

Early adopters (13.5% of the population): this is an educated group of people who are often young rather than old. They are social leaders in their community. The second group to adopt an innovation is made up of influential people who are well-liked by their peers.

Early majority (34 percent of the population): As the name implies, this group addresses a mass market where informed people begin to adopt the product. The third group to adopt an innovation consists of people who are sceptical of new ideas but are willing to adopt them if evidence of their effectiveness is provided.

Late majority (34 percent of the population): the product is eventually accepted by a large but sceptical and traditional group of people, often drawn from the lower socioeconomic classes. Individuals who are sceptical of new ideas and only adopt them when they become the norm comprise the fourth group to adopt an innovation.

Laggards (16% of the population): after everyone else has accepted the new product, those who have resisted it to the end eventually give in. Individuals who are resistant to change and prefer traditional methods of doing things comprise the final group to adopt an innovation.

The diffusion of innovation theory also suggests that certain factors, such as the complexity and relative advantage of the innovation, the compatibility of the innovation with existing values and practises, the availability of information about the innovation, and the social norms and networks that shape individual behaviour, can influence the rate of adoption. Innovators and marketers can develop strategies to accelerate the diffusion of new ideas and technologies by understanding these factors and the predictable pattern of adoption.

Crossing of chasm

This theory assumes a schism or chasm between the various groups identified by Rogers. Geoffrey Moore4, who began as an academic, moved into corporate management, and eventually became a consultant, promoted the chasm theory. He contends that in the early stages of a product launch, there is a significant gap between innovators and early adopters, and between early adopters and the early majority.

He considers the very first buyers in a market to be technology enthusiasts who will buy anything new just to see how it works. These geek-like individuals may not have any or much purchasing power within an organisation, so it is critical to engage beyond them and move the products into the hands of early adopters. Because of the chasm that separates the groups, this may be easier said than done.

Technology acceptance model

This theory is particularly relevant to new technologies, where the adopter must believe that it will improve their job performance without requiring a significant amount of effort. For example, when computers were first introduced, many people were fearful of the technology, believing that it would take a significant amount of effort to learn how to use these new tools and, more importantly, what effect they would have, as they could do the job just as quickly in the traditional manner. The same could be said of software, including dictation software, which is, by the way, being used to write this book.

It goes without saying that in order for someone to purchase an innovative product, they must be familiar with it. This means that the AIDA model (see Chapter 4) is critical in raising awareness, interest, desire, and action. The decision to purchase the product is based on someone’s belief that it will provide a relative advantage over the product it replaces. However, this is uncertain, and because many people are risk averse, they will delay making a decision until they have more evidence of its utility.

The diffusion of innovations

Rogers’ diffusion model has become the most widely accepted of the theories. In his work, he calculated the proportions of any population that are likely to be innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards. He proposed that the distribution of these groups closely resembles that of a normal bell curve. He divided the population into five groups, with half on the left side of the curve (people who are early adopters of innovation) and half on the right (people who embrace innovation at a later stage). However, the adopter classification is asymmetrical, with three categories adopting early and only two adopting late.

This is due to research indicating that innovators and early adopters can be identified as distinct groups, whereas laggards are homogeneous.

There are numerous innovations that never get off the ground. A ‘tipping point’ – a proportion of people who find the new product appealing and in sufficient numbers to spread the word to the next group – is required for an innovation to gain traction among a large group of people. It is widely assumed that the tipping point exists between early adopters and early majority, that is, when 16% of the population has accepted the innovation.

At this point, there is a chasm that, if not crossed, will mean that innovation will begin to wither. In some markets, the spread of ideas is rapid. This is the case with toys and electronic products, which quickly capture the imagination of a large enough number of people to cross the chasm and spread rapidly throughout the larger population. There are numerous examples of electronic and digital products that have made their inventors multimillionaires in a matter of years.

Many other products can take years to develop and reach the market.

Carbon fibre was invented in the 1950s, but its use was limited to sports equipment and a few other applications for nearly 30 years before it was accepted in aerospace engineering. Even now, it will be many years before it progresses past the early adopter stage. Graphene, a new material that is ultra-lightweight yet stronger than steel, was invented in 2008. A product like this requires time to prove its suitability in various applications as well as its ability to be mass-produced easily and cheaply. It will most likely be many years before this reaches the end of the diffusion curve.